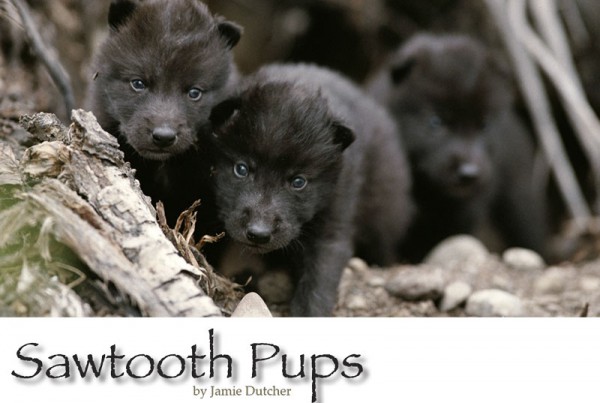

The wolf is a frequent presence in the mythology of many Native American cultures, both original inhabitants of this continent and both suffering greatly after the arrival of Europeans. To honor their primal connection, we came up with the idea of giving the pups Native American names.

Of course, we never made any attempt to teach the wolves their names; we used them only as a means to tell them apart amongst ourselves.

Most of the names came easily, based on behavior or appearance, but there was a little black female that was a bit more difficult to name. Our small crew began calling her “Black Lassie.” It was not the kind of name that stirred the imagination, but we did our best to accommodate them. Colors in the Nez Perce language are repeated, thus the word for black is chemukh-chemukh. Ayet is the Nez Perce word for girl. Thus Chemukh-Chemukh Ayet was the closest thing to Black Lassie we could come up with. After about five minutes, her name was simplified to Chemukh.

Jamie and I had always believed that Wyakin, Chemukh’s littermate, was a shoo-in for alpha female. As a pup, she had always dominated Chemukh and continued to do so into the winter of their second year. In fact, Chemukh was so shy and submissive and was having such a difficult time assimilating into the pack that we thought she would more than likely assume the omega female position. In the first few weeks of 1996, she was still a timid little wolf, the last to eat and the first to be picked on.

As January came to a close, things changed abruptly, as though a switch had been flipped inside Chemukh’s head. Her competitive instinct kicked into high gear, and she decided that it was time to assert herself. Wyakin seemed completely confused by Chemukh’s sudden aggression, for although she had been the more dominant of the two, her overall disposition was really quite sweet and gentle. Chemukh, on the other hand, was dead serious.

There was always a lot of growling and flashing of fangs. Chemukh suddenly began to push her way into the act and changed all that. She would throw herself in to the middle of the fray, grab hold of Lakota’s thigh and shake her head violently. Even Amani, whose dominance over Lakota was most severe, never behaved in this way.

It was as if Chemukh knew that the stakes were high and that she had to improve her status as quickly as possible.

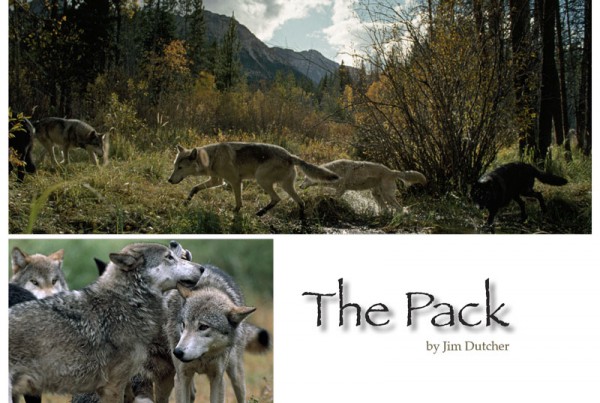

There are plenty of wonderful things to say about wolves, about the way they communicate and care for each other. Unfortunately, the competition for the alpha female is not one of those things. There is no way to sugarcoat it. It is a brutal competition for the right to pass on one’s genes. The males are comparatively laid back, sorting out their status through threats and bluff. The females draw blood.

To say that the alpha male chooses his mate is really an over-simplification. In our observation, one female eliminated the competition, placing herself, for all intents and purposes, as the only choice for the alpha male to make. Chemukh did this in a variety of ways, the least pleasant of which was to attack Wyakin’s hindquarters, making it, I’m sure, rather painful for her to breed.

Jamie and I did try to remain clinical and unemotional but it was difficult to watch. Plus, we could not help but play favorites. We really hoped that, in the end, sweet Wyakin would come forward to take the alpha position, but sadly, sweetness does not an alpha female make. Wyakin, as spirited as she was, was not up to the challenge. Chemukh was unrelenting in her offensive and, when she came into heat a few days before Wyakin, that really sealed their fates.

Kamots quickly fell under Chemukh’s siren spell. His affections were secured, and we watched Chemukh transform from a snarling hellcat to a demure little princess. Suddenly the two were inseparable. Kamots followed her closely, sniffing and licking her. They sat for hours side by side, licking one another’s faces and grooming one another.

Chemukh had completed her job attracting Kamots and now his duties were just beginning. Females remain in heat for roughly seven days and the other males in the pack were not about to control their own urges. It was up to Kamots to keep all other suitors away from his mate. If any of the males so much as wandered close to Chemukh, Kamots would attack them with such force as to make his threats over an elk carcass look downright playful. The interloper would let out a shriek of submission and retreat in a crouch. Kamots never really hurt another male but he left little doubt that this was very serious business.

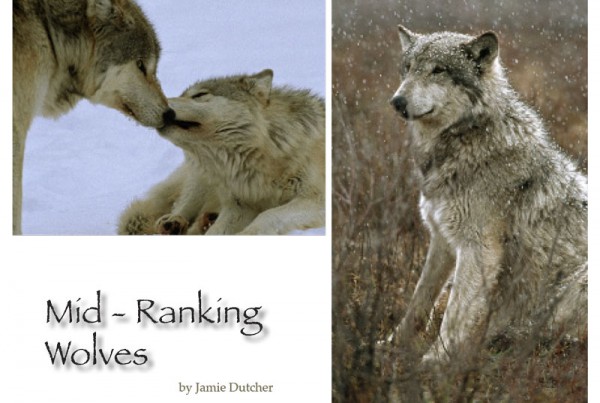

For a solid week, the torturous desire among the males was palpable. We have never heard the wolves more vocal. Over and over, throughout the day and night, they would erupt into a chorus of urgent and plaintive howls. Matsi, Amani and Motomo paced back and forth just far enough away from Chemukh to avoid incurring Kamots’ wrath. From time to time, they would snarl and bicker with each other, looking every bit like greasers at a highschool dance. Lakota was so aware that tempers were short that he left the scene entirely and waited for the frenzy to blow over. Wahots hung close by in rapt fascination, but as close to the bottom of the social heap as he was, he didn’t dare make waves. In this volatile time, the mid-ranking members of the pack didn’t need much provocation to turn them aggressive.

All this excitement enabled us to see another side of Wahots’ personality. It was strange and wonderful to witness just how much pack hierarchy means to a wolf, even a subordinate like Wahots. He kept a close eye on Chemukh, watching her as she repeatedly mated with Kamots. Unlike the other males, his behavior revealed more curiosity than desire. Kamots had been guarding his mate practically without rest for a week and was completely exhausted. When another wolf distracted him, Motomo saw a window of opportunity, threw caution to the wind, and attempted to mate with Chemukh. Chemukh, wasn’t really willing, but she wasn’t exactly fighting Motomo off either. Oddly enough, this proved terribly upsetting to Wahots who let out a plaintive bark-howl. It was the strangest sound we ever heard him make, a call of severe distress. The noise immediately caught Kamots’ attention. He turned, and launched himself at Motomo, growling terribly as he made his attack. The dark wolf practically did a backward somersault off Chemukh and scurried for cover.

That night, Jamie and I were huddled in our bed, staving off the February cold and trying to get some sleep among the choir of desperate wolves. Finally at about 2:00 a.m. the pack calmed down and we began to drift off to sleep.

Suddenly, Wahots’ same bizarre cry tore us from our sleep. It was followed quickly by the sound of heavy paws galloping across crusted snow, and then a terrible crashing and snarling as Kamots collided with a wolf, probably Motomo once again.

We had become so familiar with these wolves that even in the darkness, without leaving the comfort of our tent, we could picture precisely what was happening. To our amazement, it seemed as though Wahots was actually “tattling” on Chemukh, making sure that Motomo would never be able to mate with her. This little commotion sparked a new round of howling, growling and complaining that didn’t let up until dawn.

For many days, we mulled over the possible reasons why Wahots was snitching on Motomo and Chemukh. He was dangerously close to relieving Lakota from the omega rank and it was possible that he was trying to curry favor from Kamots. Another answer could be that Wahots simply could not stand to see the pack hierarchy violated. Every wolf in a pack knows its place and the places of all the other wolves. Without the hierarchy the pack falls apart. Wolves may challenge one another within the system but they do not disobey the system itself. Wahots knew the rules, and the rules dictated that he could not mate with Chemukh no matter how strong the desire. If he couldn’t do it, then, by golly, Motomo couldn’t either.

Wyakin came into heat shortly thereafter, but the males did not pay nearly as much attention to her as they had to Chemukh.

It was strange and wonderful to witness just how much pack hierarchy means to a wolf.

For one thing, Wyakin was not advertising herself as “available.” In the previous days, Chemukh so successfully dominated her that Wyakin was too afraid to solicit any attention from the males. If a male approached her with intent to mate, Wyakin would run away or sit down and refuse to budge. It was either that or risk having Chemukh bite her hind quarters again.

Kamots had no interest in mating with Wyakin, but he still wasn’t going to allow any of the males near her. Though not with the same conviction, he chased the males away from Wyakin as he had done with Chemukh. This would draw Chemukh’s attention and she would lay into Wyakin just for good measure. For the rest of the breeding period, Wyakin kept a very low profile.

It is common behavior in a wolf pack for the alpha pair to be the only pair to mate. It keeps the numbers in control, for too many wolves in the pack, especially puppies, would be a liability. Many hungry mouths and not enough hunters means they could all suffer. Instead, each wolf devotes itself completely to the few puppies that are born to the alpha pair, making sure they grow up to be strong and beneficial additions to the pack.

This is not a hard and fast rule. In some packs, the beta pair will be able to breed – it really comes down to what the alpha pair will allow. Generally, their decision has to do with the availability of a prey base. If food is plentiful, the alpha pair may decide that the pack can handle a few extra members and allow the beta pair to breed. When times are hard and food is scarce, even the alphas may choose not to breed. Whatever variables may exist in the wild, however, Kamots and Chemukh held to the standard model and would not tolerate any amorous behavior among the other members.

As the winter months progressed, Chemukh became more and more preoccupied with choosing the perfect site for her den. A den’s only purpose is as a place for giving birth and protecting newborn pups. The job of constructing it falls exclusively to the alpha female, for it is her domain alone. Chemukh seemed to have an instinctive set of specific criteria in her head. She would select a spot, dig for a while through the snow and earth, then decide that it was not the right place after all. Perhaps the soil was too loose or too rocky, or perhaps the ground held too much water. Something about it failed to suit her. The rest of the pack dug as well, not that they were helping Chemukh; they just dug shallow pits in any old spot, caught up in the spirit of the occasion.

Having lost the battle for the alpha position, Wyakin settled gracefully into a supporting role. Like a midwife, she became very attentive to Chemukh, grooming her or just sitting by her side. Kamots, on the other hand, was not particularly attentive to his mate. He had done his duty and was back to the business of protecting the pack and patrolling his territory.

Finally, Chemukh settled on a site at the high end of the enclosure in a heavy grove of spruce. A fallen tree had created a natural cavity and a perfect place for her to modify as a den. With an air of great importance Chemukh disappeared into the hole and a second later clumps of dirt began to fly out of the entrance. She kept at her work for several days. We knew the den must be cavernous but we avoided the urge to peek inside lest our presence cause her to abandon the project.

There was still over a foot of crusty snow lingering on the valley floor on April 22, 1996, the afternoon that Chemukh separated herself from the pack and disappeared into the spruce grove. She slipped away so inconspicuously and quietly that none of the other wolves followed, and Jamie and I failed to even notice.

The next morning, there was not a single wolf in sight around our camp. We hurriedly threw our clothes on and hiked up to the grove. The pack was milling around the area with an air of great excitement. As we walked to the den, they followed us and peered into the tunnel alongside Jamie and me. Inside, we could hear the delicate cries of newborn pups.