Watching the way wolves interacted with one another, it was easy to see why so many early human cultures revered wolves.

Watching the way wolves interacted with one another, it was easy to see why so many early human cultures revered wolves.

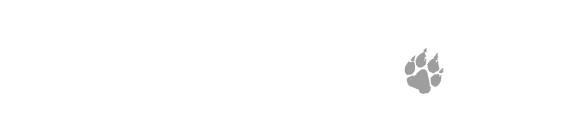

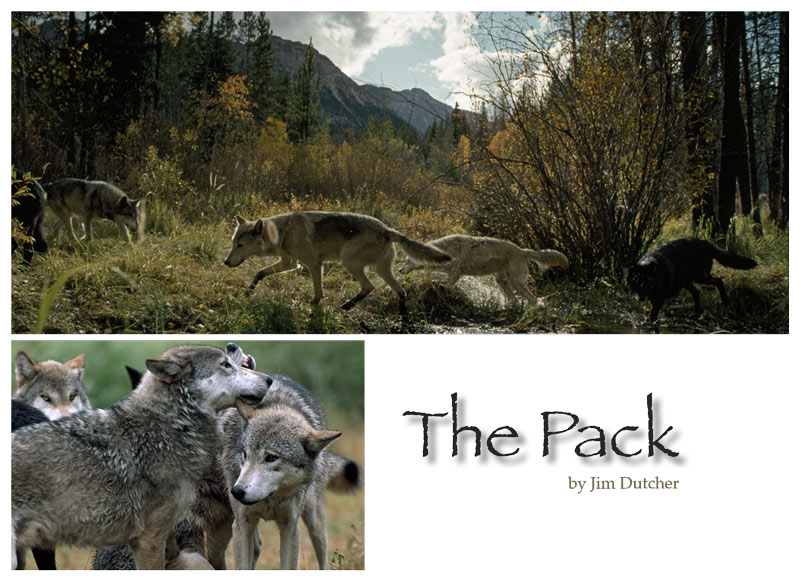

Hunting societies especially admired and even imitated the wolf ’s skill, for as predators, human beings and wolves have similar limitations and must employ similar techniques. It is during a hunt where wolves’ near telepathic co-operation is most apparent. A wolf pack may trail a herd of elk, caribou or other large prey for days before making its move. During this time, they are already hunting, assessing the herd, looking for an animal that displays any sign of weakness, and this is just the beginning.

Wolves must also factor in other conditions that will affect the hunt; weather and terrain can tip the scales in favor of predator or prey. For example, a wide open plain favors the ungulates, who, if full-grown and healthy, can outrun the fastest wolf. On the other hand, crusty snow or ice favors the wolves whose wide round paws have evolved to perform like snowshoes and carry them effortlessly over the surface. An experienced wolf is well aware that hoofed animals break through the crust and can become bogged down in deep snow.

Wolves have learned to use these conditions to their advantage. A biologist friend told me of a particular pack in Alaska that he has observed following a herd of caribou on a narrow packed trail through deep snow. The wolves know that their mere presence, following close behind, will eventually panic the caribou. When the rearmost caribou spooks, leaving the hard trail and attempting to run to the middle of the herd, it founders in the snow drifts. When that happens it is all over. In warm weather, this same pack of wolves changes its tactics, herding the caribou into a dry river bed where many of the ungulates stumble on the round stones.

A wolf pack therefore weighs many different factors when selecting its target and, as circumstances change during the hunt the target may change as well. Initially they may be pursuing a calf, but if a big healthy bull stumbles unexpectedly, they all know to go after the bigger meal. Conversely, if too many factors seem to be going in favor of the prey, they may choose to wait. Sometimes it is better to stay a bit hungry until the odds improve rather than expend precious energy on a fruitless chase.

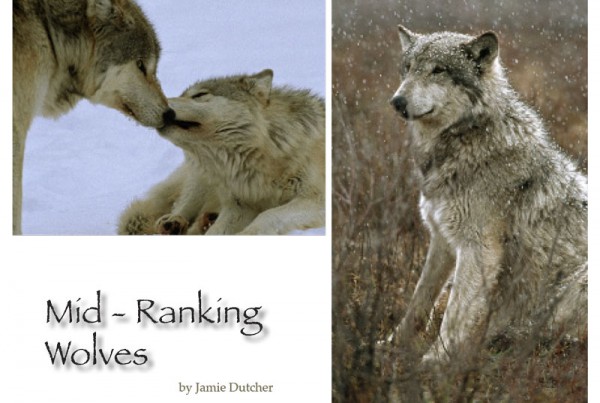

Other observers of wild wolves have reported that often fewer than half of wolves on a hunt are actually involved with physically bringing down the prey. The youngest wolves frequently do nothing more than observe and learn from the sidelines. Each of the other pack members contributes according to its particular experience and ability. Speedy, lightly-built females often take on herding roles, darting back and forth in front of prey, causing confusion and preventing escape. Slower but more powerful males are able to take down a large animal more aggressively and quickly.

Some of the wolf’s bad reputation stems from the apparent mob scene that ensues when the prey begins to falter. Wolves are not equipped to dispatch their victims quickly; prey usually die of shock, muscle damage or blood loss. If it can, one of the stronger wolves will seize the prey by the nose and hold on tight, helping to bring about a more expeditious end, but the animal can still take many minutes before it succumbs.

Equipped only with feet for running and jaws for biting, wolves make the best of their limitations. A wolf pack’s ferocity and apparent brutality is really a defensive measure. It is not rare for a wolf to be seriously injured by flailing hooves and slashing antlers. A well placed kick could break a wolf’s jaw, rendering it unable to feed itself. It is much safer to harass the prey and let it tire out before moving in close. Far from being a mob scene, a hunt is a masterfully coordinated group effort, well deserving of our admiration.

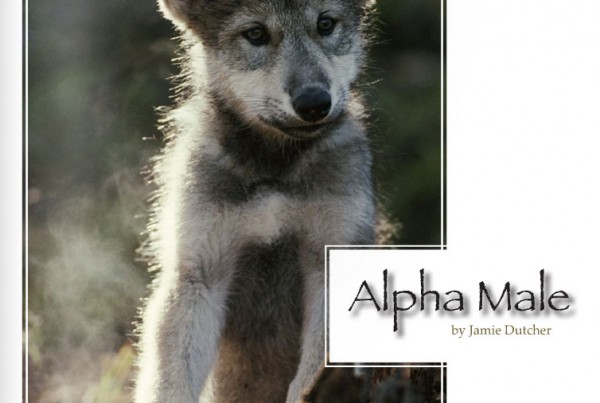

Although the alpha male is usually in the thick of the hunt, it would be an exaggeration to say that he is leading it. The alpha may select the animal to be pursued, or he may chose to break off the hunt if it is going poorly. But he is not barking out orders to his subordinates like a general on the battlefield. The wolves just seem to know what to do, and they do it as one.

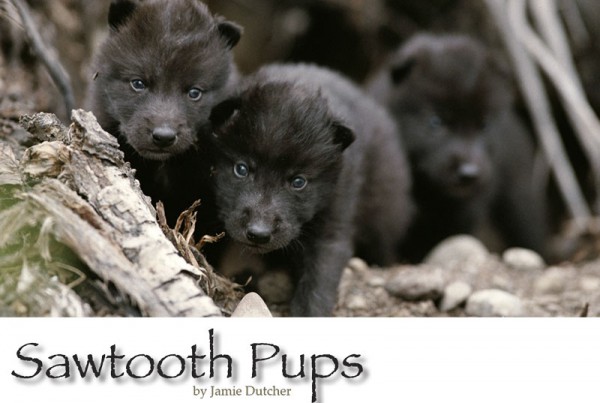

People understand that wolves are predators, but many still do not know the other side of wolves, a side that the animal does not readily share.

Our project, by its very nature, had its limitations. The animal’s prowess as a hunter was one aspect of wolves that we were unable to feature. Nor were we able to show certain other qualities such as the great distances they can travel or the way packs defend their territory. These limitations were balanced by our ability to examine their personal relationships with one another, and it was here that the more subtle signs of pack unity revealed themselves.

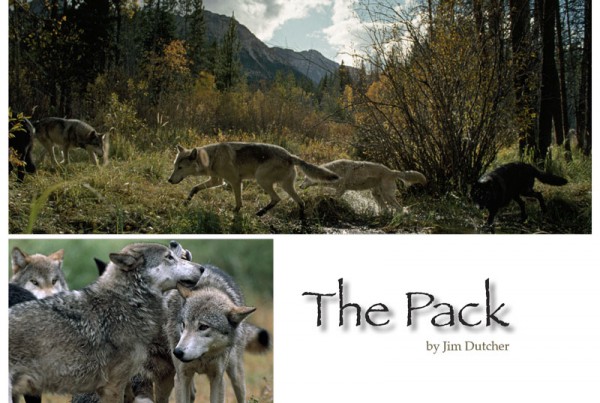

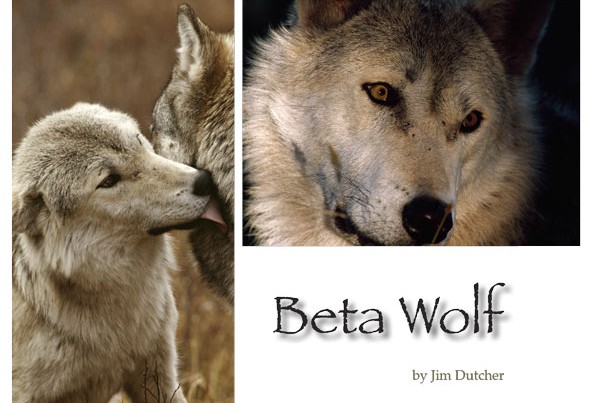

Rarely did two wolves pass one another without playfully rubbing shoulders together or exchanging a brief lick. So often Jamie and I would see two wolves relaxing together, curled up beside one another, the head of one wolf draped over the neck of the other in a gesture that was both assertive and affectionate. More than hunting or travel, this is the behavior I hoped to reveal in my films because it is the side of wolves that people understand the least.

After observing this pack for so long, I have come to believe that the bond a wolf has to its pack is certainly as strong as the bond a human being has to its family.

One would hope that this similarity would give us an instinctive sympathy for wolves, but we stubbornly resist granting another creature qualities that we cherish as singularly human.