Keeping Livestock Safe

There are many ways to keep wildlife and livestock safe when both are living side-by-side in wild places. An assortment of tools and techniques, known as “non-lethal deterrents,” are proven effective in keeping native predators (wolves, bears and mountain lions) away from cattle and sheep being raised for human consumption. When these tools are not used, sometimes predators will attack livestock.

Where And Why Do Conflicts Occur?

In the West, there are hundreds of millions of acres of public lands – lands owned by the citizens of the U.S.A. These lands are emblematic of the West, a mosaic of magnificent landscapes, expansive deserts, forests, mountains and canyons that host native wildlife in diverse, often fragile, ecosystems.

The U.S. Forest Service is responsible for the stewardship of a large portion of these public lands, overseeing more than 80 national forests in the West. This is where wolves, bears, coyotes and mountain lions live. And they all play a vital role in the health of both the land and the wildlife. But national forests are also managed for “multiple use.” This designation allows for the grazing of privately-owned livestock on tens of millions of acres of publicly-owned national forest lands.

Livestock are turned out onto public lands every spring, and then rounded up in the fall after a long season of grazing on native vegetation. Many millions of cows and sheep graze the public lands of the West. More than any other state, 38.2% of Idaho is national forest. There are 230,000 sheep and 2.5-million head of cattle in Idaho alone, which amounts to roughly 30% more cows than people, or about four cows for each elk and deer combined. Cattle are often left unattended on the range for weeks or months, with very little human presence throughout the duration of the season.

Given this reality of land use, it is remarkable how infrequently wild predators, like wolves, bears and mountain lions, attack livestock. While these animals must hunt to survive, even amid such an overabundance of domestic livestock, predators tend to stick with hunting their native prey. But livestock are known to displace native prey animals like deer and elk, and, under certain circumstances, conflicts do arise. And when predators get near livestock, the predators are often killed.

Western states, and especially Idaho, are hard on wolves in this regard. But this technique of reacting to conflicts by killing predators, rather than preventing conflicts from happening in the first place, is deeply flawed. If a predator kills domestic livestock, a producer loses an animal, and the animal loses its life. Then efforts are made to kill predators in the area, carried out by a branch of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, inappropriately named Wildlife Services. There is no reliable way to determine if the animal, or animals, in Wildlife Services’ crosshairs were actually responsible for the attack.

For the animal that committed the attack, there is also a strong likelihood that it was providing for more individuals than just itself. Killing a mountain lion or bear can result in orphaned lion or bear cubs that may not yet have the necessary skills to survive on their own. The loss of a single wolf can spell the end of an entire pack. Killing predators can have devastating consequences and could lead to death or desperation for the survivors and possibly even more trouble with livestock.

A better and more proactive solution is for livestock producers to use non-lethal deterrents. Livestock and predators are kept separated and alive, when non-lethal deterrents are used. The main obstacle to their success has been the unwillingness of producers to use them. But in places all across the West, there are examples of livestock operations putting these techniques to use.

Unfortunately these practices are not as widespread as they could be, and certain places lag behind. According to the latest data from 2015, only about 6% of all livestock operations in Idaho experience attacks from predators in a given year. Yet, Idaho still kills more wolves for conflicts with livestock than any other state. And when it comes to preventing attacks, Idaho does less than any other state where wolves live to prevent conflicts, with only 10.1% of cattle operations using even one form of non-lethal deterrent.

What Are The Non-Lethal Deterrents?

People have been raising livestock for at least 10,000 years. And, over that time, they have developed many methods to protect their animals. The most effective has always been human presence. Most wild animals fear people. They keep their distance and leave when humans approach. The same is true for wild predators.

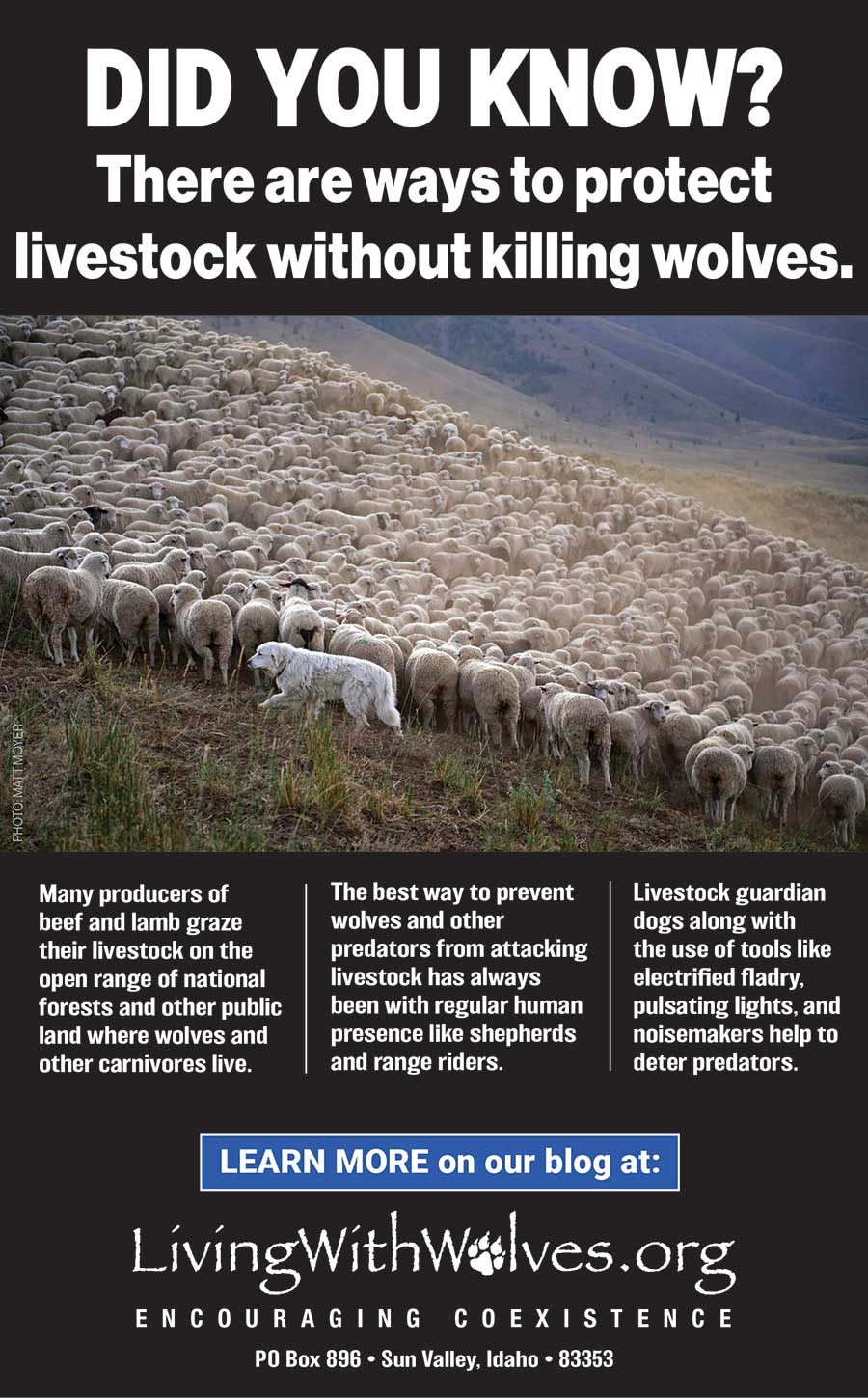

Whether shepherd, cowboy, herder, vaquero or gaucho, there are terms around the world identifying people who attend domesticated livestock. In terms of protecting their animals, these people all serve a similar purpose. Their mere presence, whether on foot or on horseback, is typically all that is needed to keep predators away. Today, “range rider” is a broad term used to describe a person who fills a variety of duties related to keeping track of cattle while preventing conflicts.

But human presence isn’t always possible and, on its own, isn’t always enough to keep livestock safe on the open range. The domestication of wolves, the animals that became our dogs, preceded the domestication of livestock. It is likely that dogs have been assisting us with our livestock since the beginning.

Livestock guardian dogs are working dogs that, depending on the breed, serve different purposes, but fundamentally, they are watchful protectors. They know their role and perform it well. Barking is meant to sound an alarm, which can awaken a sleeping herder or alert them to a threat they may have not otherwise detected. Some dogs will take up a defensive posture to physically protect the herd. Alongside livestock guardian dogs, herding dogs work to keep the livestock animals together. Working dogs are an especially common way of keeping sheep safe and moving together.

Over the past 10,000 years, domestic livestock have lost or forgotten many of their natural defenses. One such defense is the natural herding instinct. While it is strong in many wild animals such as elk, bison and caribou, it has waned in domestic livestock over millennia. Safety in numbers is a necessary survival instinct in the presence of large predators. Some cattle operations are working to reawaken this instinct. Cattle that stick together are much less vulnerable to attack than cattle distributed across large landscapes.

Most livestock deaths are not the result of a predator attack but rather the result of disease, weather, or birthing complications. Another proactive way livestock producers can mitigate potential conflicts is to remove the carcasses of dead livestock. Carnivores like wolves, coyotes and mountain lions, and omnivores like bears will be attracted to the smell of a dead animal and may find and follow the scent from miles away. It is also important that these opportunistic scavengers do not learn to associate living livestock as a food source by becoming comfortable scavenging on carcasses of dead cattle and sheep.

There are other technological solutions, both new and ancient, that help keep livestock and predators separated. Using corrals or sheds for birthing protects newborn calves and lambs and their mothers. Most attacks occur during the night or the few hours of twilight. Night penning in similar structures, or bringing the herd together reduces exposure at night when risk is elevated. When animals are grazing in national forests, a temporary solution is needed. Mobile fencing called fladry, consisting of nylon flags hanging from cording, can be strung up in relatively short order, allowing for mobile penning. The movement of the flags is surprisingly effective in preventing a breach of the perimeter. For extra security, the cording is also often electrified.

Temporary fladry pens used with strategically placed strobe-like lights that flash erratically, have also shown to be remarkably effective in keeping predators from coming in for a closer look. Loud noise-makers such as air horns or starter pistols are also effective in driving away predators.

Society has become less tolerant of killing native wildlife in the interest of private business, especially in the wild places and on public lands where people want and need nature to exist and thrive. Old and new practices and tools are making it possible for coexistence.