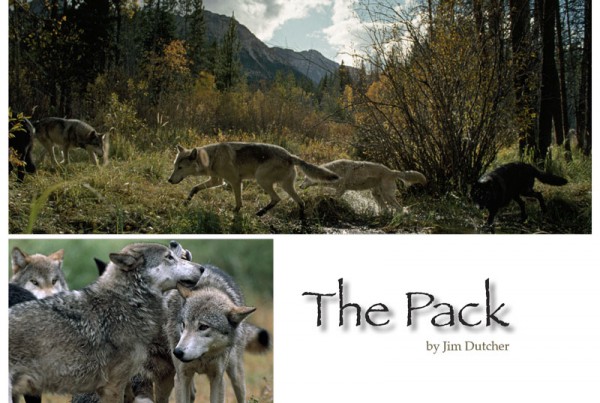

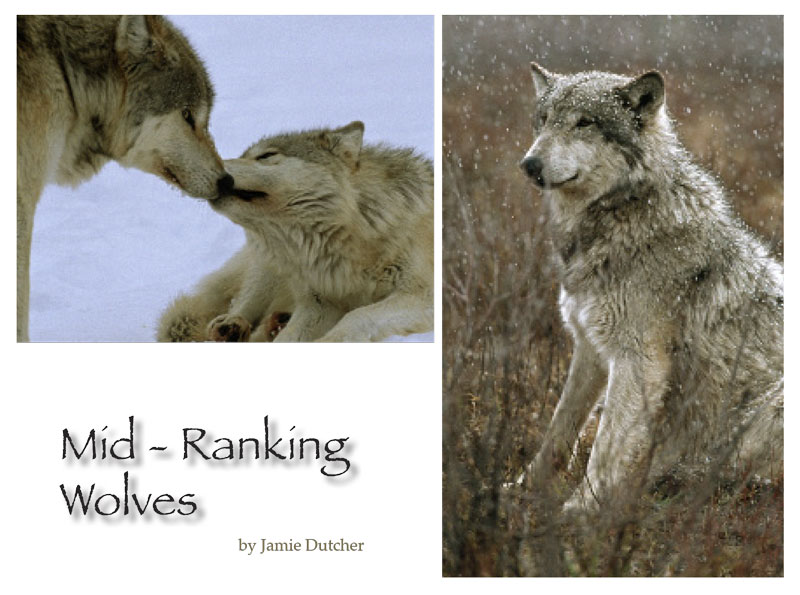

Most wolves are mid-ranking, filling the vague area below the beta and above the omega.

Most wolves are mid-ranking, filling the vague area below the beta and above the omega.

The rank of these wolves is more difficult to determine through observation because it appears to be rather fluid. All the same, within the middle echelons no two wolves have exactly the same rank, and these ranks may change from week to week.

It is extremely difficult for a mid-ranking wolf to depose a well established alpha or beta. However, there is always hope of moving up a peg or two in the pecking order and improving one’s lot ever so slightly.

For this reason, much of the squabbling in the Sawtooth Pack occurred within the middle ranks.

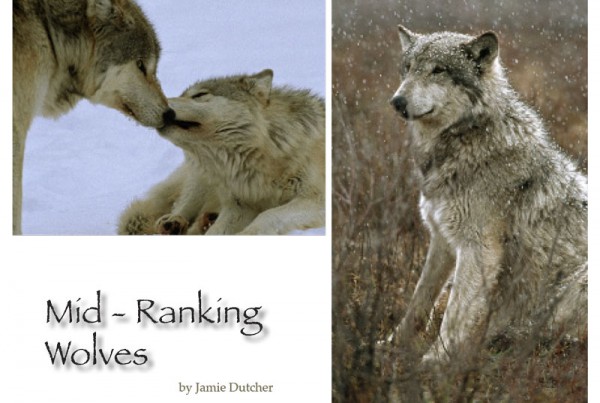

Over the years, the pack grew in size and the middle echelons became more complex, but the two older wolves that epitomized this nebulous and volatile group were Motomo and Amani. Their brother Matsi had solidly established himself as the beta wolf, effectively sealing off any hope for social climbing. The only other option left to them was to descend in rank, and it was easy to see that neither of them was about to do that. Consequently they jockeyed for position with each other, trying to assert themselves as the more dominant of the two. When that got old, they resorted to displaying dominance over Lakota just to remind the rest of the pack that they were definitely not omega material. During my years with the pack, I would only have been able to guess at which of these two was really dominant and which was subordinate on any given day, but I’m quite sure that they knew.

Motomo was the darkest wolf of the pack, jet black with a white patch on his chest. Of all the wolves, he seemed to take the greatest interest in the activities of people. It wasn’t so much that he craved direct contact with us, he was just incredibly curious and loved to observe us. Long after the rest of the pack had moved on to other business, Motomo would stay close by. When we walked the perimeter of the enclosure to check for fallen trees or other potential threats to the fence, Motomo usually followed us the entire way, as if supervising.

One of Jim’s photographs that became a successful poster is a head-on shot of Motomo in which he is lying in the snow and staring directly into the camera with his deep yellow eyes. That is exactly the way I remember him, sitting completely still and scrutinizing us intently from a few yards away as we set up our camera gear, split wood or shoveled snow. At times, he really appeared to be trying to figure out what on earth these strange primates were up to, always scurrying about, always busy.

There was something wonderfully dignified about Motomo. He enjoyed our company but kept his cards close to his chest. He wasn’t going to lower himself to the point of actually soliciting our attention. His brother Amani couldn’t have been more different.

In both appearance and demeanor, Amani was a near opposite of Motomo. He had the perfect markings of a classic gray wolf: mottled gray fur with a black mask, a pale muzzle and throat, and rich caramel eyes. Where Motomo was dark, mysterious, and rather reserved, Amani was all flash and showmanship. He was a little like the class clown, the kid at school who would do anything for attention.

However, when it came to social status he was dead serious and could be a downright bully. As he did when he played the clown, Amani approached social competition with great flair, making sure that he had an audience. Oddly enough, when Amani was a yearling, he was the shyest of his siblings. Perhaps this fear lingered with Amani and he continually felt the need to prove himself.

Unfortunately, the wolf that was almost always on the receiving end of Amani’s posturing was Lakota. Amani would use any available opportunity to demonstrate his dominance, sometimes even pouncing on Lakota out of the blue when all was otherwise quiet. During pack rallies when displays of dominance were common, Amani could be counted on to lay into Lakota with special zeal. Once he started, Motomo, Chemukh, Wahots and Wyakin would often get involved and make the situation all the more miserable for the omega.

Amani also seemed to dominate his brother most of the time, making a show of climbing on Motomo’s back and growling. Motomo didn’t seem to mind the fact that he was being pushed into a submissive role most days.

A man of few words, Motomo decided to save his energy for when it really counted – meal time.

As calm and docile as he was, Motomo’s personality transformed once a deer carcass appeared on the scene. It was here that we could really see who was on top when the chips were down. With his black coat and yellow eyes, he looked utterly sinister as he bared is fangs and tore into the deer or elk. Hair from the animal would get stuck in his mouth and the ensuing spitting and snorting to get rid of it made the image all the more frightening.

When Motomo moved toward the carcass to eat, he met with less resistance from the more dominant wolves than did Amani, a probable indication of their ranks in the eyes of the pack. Once Motomo was savoring the kill, he made a point of trying to keep Amani off. It was much more important to him than it was to Kamots or Matsi. He would snarl and chase his brother away in what seemed like payback for all the previous day’s dominance. Sometimes Amani was left circling the carcass for quite a while, jockeying for position and taking out his frustration on Lakota.

There were rare occasions when Motomo and Amani set their competition aside and joined forces for their mutual benefit, at least this seemed to be the case. There was one particular feeding which stands out in my mind as a time when the two mid-ranking wolves actually appeared to be cooperating so that they both could eat. On a crisp October morning, we brought the pack a young deer that had been killed on the highway a few days earlier. They had recently eaten but since the deer suddenly became available, we brought it to them.

Wolves in the wild are used to eating this way, bringing down kills of different size at irregular intervals.

Still, this unusually small meal heightened competition over the carcass. The only ones really to get their fill were Kamots, Matsi, and the pups, Wahots and Wyakin. Lakota and Chemukh were going hungry on the sidelines and Motomo and Amani were frantically sniffing around the scene, snatching up any scraps that had been inadvertently cast aside.

I heard them vocalizing to each other in an exchange of frustrated whines, and at the same moment they turned toward Kamots who was towering over the carcass. The small deer had been torn to shreds and nearly consumed. All that remained were two disembodied hind legs and a portion of the torso. Kamots appeared to be intent on finishing it all. As the two mid-ranking wolves faced Kamots he uttered his warning growl, telling them to not even think of approaching the deer. They whined back to him, or to each other, appearing to be begging for food.

The scenario that followed occurred with such incredible speed that it stunned us as much as it did Kamots. Looking as if he had been shot from a cannon, Motomo dashed directly at the carcass and grabbed a small chunk of fur and meat that was lying off to the side. Kamots took the bait and chased after him for a few feet, momentarily leaving the carcass unattended. Capitalizing on the tiny window of opportunity, Amani rushed in and snatched one of remaining deer legs. Seeing his mistake, Kamots turned, but not fast enough. Amani clung to his prize and made a bee line for the willows with Kamots, now close on his tail. What was most fascinating is that, instead of continuing to eat his small chunk of meat, Motomo dropped the morsel (much to the pleasure of Lakota), and turned back to the carcass. He grabbed the other hind leg without breaking stride and veered off in the opposite direction. This final maneuver bewildered Kamots so completely that he broke off his pursuit of Amani and returned to stand guard over what was left of his deer.

This interaction was the subject of ongoing debate and discussion in the days that followed. It could well have been that what we had witnessed was an “every wolf for himself” situation in which both Motomo and Amani were able to capitalize on the chaos. However, it was all so perfectly timed and adeptly executed that there seemed to be more to it than mere chance and opportunism. The way they approached Kamots together, the unusual vocalizations they made to one another, the way Motomo dropped his “decoy” piece of meat the instant Kamots’ attention turned toward Amani: these factors indicated to me that they had actually hatched a scheme and deftly pulled it off.

It is hardly a far-fetched suggestion that Motomo and Amani had worked together. After all, a wolf’s strong cooperative nature is perhaps its greatest survival skill. A solitary predator like a cougar is physically far better equipped for hunting than a wolf is. With its sharp claws, a cougar can grasp its prey long enough to deliver a suffocating bite to the throat. Its forelegs are powerful enough to snap the neck of large elk.

Wolves may lack a cougar’s power, stealth and weaponry, but they do possess one great advantage – each other.

Had they been part of a wild pack, Motomo and Amani’s cooperative efforts would have served them well in the hunt. They would have been the grunt labor, in the thick of the hunt, getting the job done. But these two also taught us that being a mid-ranking wolf has no similarity to being a foot soldier, part of a large force of equal “worker bees.” In a wolf pack, there are no equals. Someone always has the slightly upper hand, even if it changes from day to day, and there is always the chance of moving up the ladder a rung or two.