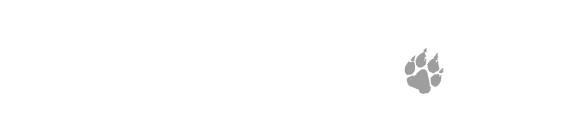

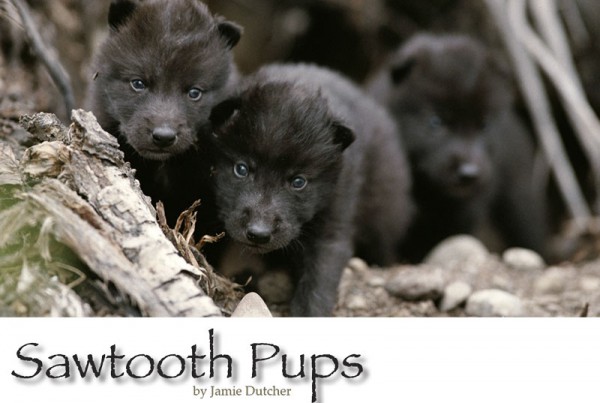

On certain occasions when the pups were from two to four weeks of age, we would separate one pup or another from the litter to socialize them and help them feel safe around humans. When we removed Kamots’ brother, Lakota from his littermates, he become nervous, afraid to explore and anxious to get back among his siblings. It was not so much that Lakota was afraid of us, it seemed more that he feared that the other pups might not accept him back. When he was returned to the others, there would be several minutes of squabbling amongst the pups, as though Lakota were vying for his social position all over again.

Kamots, on the other hand, positively seemed to enjoy the chance to get out and explore.

He would confidently inspect his human caretakers and investigate anything within reach of his inquisitive nose. He returned to his littermates calmly, free of doubt, his position assured.

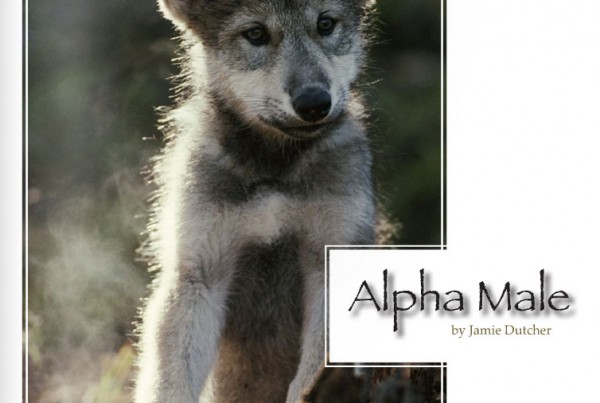

As he grew, Kamots did not have to fight for the top spot. When he reached full size, he simply assumed the mantle. There was never any doubt in his mind or in the minds of the others that he should be anything other than the leader.

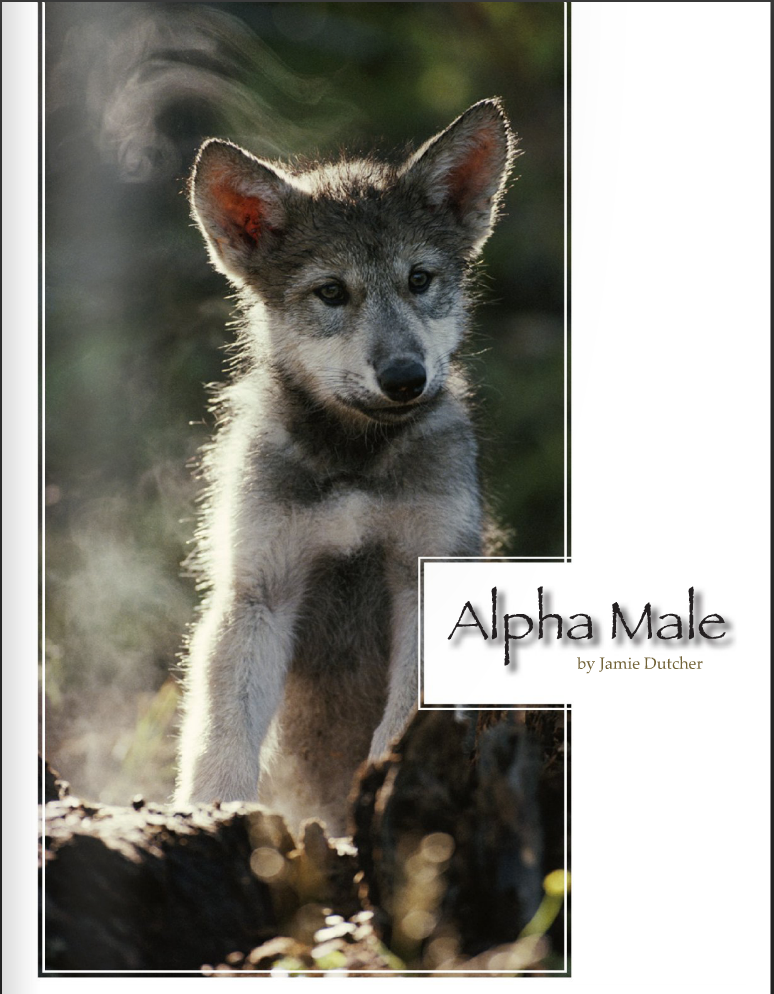

The alpha holds his tail and head high, he lifts his leg to urinate while subordinate males usually do not. He is continually vigilant, not simply responding to obvious threats but maintaining a watchful eye at all times.

Ultimately, the position of alpha male had nothing to do with age, size, strength or aggression.

It sprung from a source that we will never see and can barely hope to understand. It is a rule that the wolves themselves know, accept and live by.

Kamots was a marvelous leader. The confidence he had shown as a pup blossomed into a calm benevolence that was a joy to witness. There was an alertness about him not present in the other wolves, and his face often bore an expression that, at least to people, registered as concern. When a strange sound rang out in the surrounding forest Kamots was the first to prick up his ears and trot off to investigate. Perhaps the rest of the pack did not behave this way because they knew they didn’t need to. They knew Kamots would keep them safe.

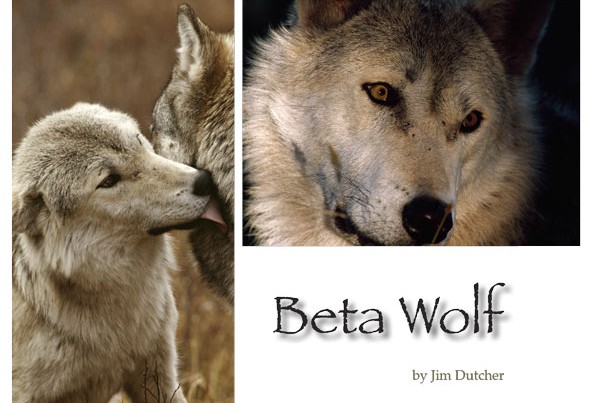

Despite his benevolence, his rule was supreme, and he did not hesitate to make it known.

His command over a deer carcass and his possessive displays were really quite terrifying to behold. The first time I saw Kamots distort his face in threat I was amazed. It was during a feeding, and I had shot slow motion footage of Kamots presiding over the kill. Lakota timidly attempted to approach the carcass and eat before his turn. Kamots raised his eyes from the meal and let out a loud growl, baring his teeth but keeping them fixed on the carcass. Despite the warning, Lakota pressed on. He seemed to think that if he could just make himself insignificant enough, he could sneak a bite or two before anyone noticed. In an instant, Kamots’ features twisted into a mask of ferocity. He raised his lips high, exposing the full length of his teeth, his nose pulled back and his ears shot out to the sides like horns. His graceful muzzle became short and broad, making his jaws seem all the more powerful. With a savage snarl, he charged over the carcass at Lakota who scurried a few paces before flipping over onto his back with a yelp of submission. The question of who would eat when was quickly settled.

Law in a wolf pack can certainly be tough, but I never saw Kamots behave with anything that resembled viciousness. In this particular encounter, Kamots’ teeth never made any real contact with his brother, it was mostly show. Over the years, I have seen other wolves tear into a subordinate with an obvious intent to do physical harm. The abuse that one wolf can subject another to is often hard for human observers to bear. Kamots certainly removed many a tuft of hair and delivered many a stern bite, but once the order of things was restored, he quickly returned to his usual calm self.

All this responsibility and authority did not impinge upon his desire to play with the rest of the pack. In fact, he seemed to rejoice in temporarily abandoning his duties and indulging in a good frolic. He was just as apt to play with Lakota as to dominate him. At times his behavior was so benign, so puppyish, that it was impossible to imagine that this was the same creature who minutes earlier had displayed such ferocity over a meal. Holding a grudge, it seemed, was not in his character. Yet even at play, there was something about Kamots that suggested that he was the leader. Sometimes he would not fully engage in the frolicking but watch the others with a protective air. In games of tag, Kamots was usually the one doing the chasing, and, in general, he would win all battles of tug of war with sticks or bones.

It was while filming Kamots at play that I observed one of the first undeniable illustrations of the concern that wolves have for one another. It was a gesture of kindness

that just bowled me over. Kamots was charging around the meadow, celebrating the first major snowfall of the year. Something about new snow thrilled them to no end. After it was on the ground, they took it for granted, but while it was falling they greeted it like a gift from heaven. Even late in the year, when we would hurl curses at the sky for so much as another flake, the wolves acted as if it were some fresh new surprise. As the snow began to accumulate on the frozen ground, Kamots led the festivities. He ran back and forth through the meadow, not playing tag or chasing another wolf, just darting about in unbridled jubilation. Amani, still under a year old and not full size, wasn’t quite sure what to make of the alpha carrying on like that. He sat down in the meadow and watched Kamots run in circles and disappear into the willows.

Kamots burst from the bushes at full speed and in his exuberance barreled right over his young pack mate. Amani did a cartwheel and sat up, blinking and covered in powder, not sure what had just happened to him. Kamots’ body language was unmistakable. He slammed on the brakes, turned and hurried back to Amani, sniffing the little wolf up and down and giving him a few reassuring licks. I was profoundly touched by this display of concern; it was almost an apology.

Kamots secured his leadership and maintained it for nine years using a minimum of force and aggression. I believe it was his genuine regard for the pack that made him such a benevolent leader, and his confidence that made him such a secure one. From the time he reached adulthood, he knew he was the alpha, never imagining that things could be otherwise. He never showed evidence of feeling the least bit threatened, never tried to prove himself by bullying the others, and never seemed to doubt that the security of the pack should be left on his shoulders.